Some of the trickier things we face as we grow older.

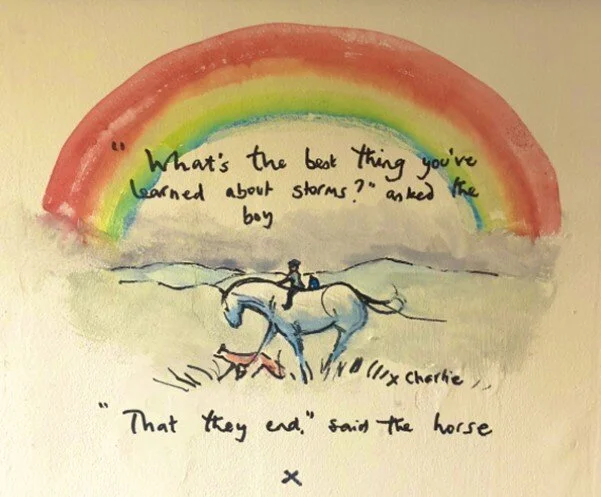

Charlie Mackesy’s book, The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse has spent 60 weeks in the Sunday Times best selling hardbacks up until the end of 2020. “This is a book for everyone, whether you are eighty or eight” he writes. This is a book about love, friendship and kindness, but it also offers hope support and encouragement to those facing fear, doubt or anguish.

The message and illustration below are not from his book but from the wall of The Black Dog Deli in Walberswick, Suffolk, which is owned by Charlie’s friends. It references the pandemic but is also a message of comfort to anyone going through troubled times.

Here we explore some of the new things we face as we grow older:

Providing Care

If you’re a boomer, your parents will be in the 80’s, 90’s or have died – mine have. At your age it will have well been discussed and you will likely have had to look at arranging some kind of care or support, and then finally, funeral arrangements.

There is no guidebook on this part of life, they don’t give you lessons at school on dealing with dementia, illness, death; all the founders of this firm are boomers, so we thought we’d share some pointers and tips – a handbook for the sandwich generation.

By the way, this isn’t intended as legal advice – if you are unsure of your legal position regarding anything discussed here then you must seek appropriate advice.

How to get a reluctant parent to sign a power of attorney (PoA).

For their generation, most folk struggled to accrue any savings at all so the suggestion of giving someone else control of the money never sits comfortably, and an elderly parent can be reluctant.

Remember they also have in mind horror stories and misinformation shared around the church coffee mornings of kids pinching the money, forcing aged parents into workhouse-like care homes to be fed gruel and put to bed at 6pm.

To start with, every time, simply inform them ‘it needs to be organised now’, leave the forms on the table and leave it alone. In good time they’ll pick it up on their own and read through it. If they’re with you, you’ll get it done with no fuss – if not, it may take several months, don’t rush it. There’s a simple outline from Age UK.

The points to make:

The common misunderstanding is that if it is signed the attorney has immediate access to everything: you should explain that the PoA can only be used when they are not mentally capable, and not before.

The second point is that if they are not capable, then the decisions will still be made on their behalf, but this time by complete strangers, either in the courts, the NHS or the Court of Protection.

The PoA means the person appointed to help will be someone who knows you – either family, or a friend or someone from church/synagogue/mosque/temple etc. There can be more than one attorney.

You need to bear in mind that a person can only sign a PoA while they are still capable – so it must be done earlier rather than later. It’s never too soon – do your own now as well.

If you’re not having any joy, then see if there is someone that they trust in the community who could join your side – in my case I asked the local vicar who did a grand job with my Mum over tea and scones at the vicarage. (If God’s rep in the village says it’s ‘a good idea’ it must be).

Be aware – rules on PoA’s have changed, and we have seen family feuds open up. Back in the day, it used to be that a new PoA had to be sent out to all the direct family to be notified and granted the power of veto if appropriate. This meant that 88 year great Aunt Maude couldn’t be whisked off by that 40 year waiter she met on holiday last year and be unwittingly talked into assigning authority over her millions if not warranted. That’s now changed, so be aware that a parent can appoint one of the children without telling any of the others. It happens.

Introducing care to a defiant parent

Defiant? Stubborn? Strong willed? Proud? (Yep, that was my Mum).

Think like an 80-/90 year old – they are not always chuffed by the marker in their ever shrinking lifespan that is the introduction of the need for care. You don’t get better from needing help in the house, feeding yourself, getting dressed or bathing. “The carer is a big flag pointedly showing to all my neighbours and friends that I can’t look after myself’.

Your parent has a good point. Their daily competence is very different seen through their eyes – they’ll say ‘I’m fine’ (sound like anyone you know?) but you might not agree. There is a little of the situation that’s the same when you were a teenager – the competence you thought you had was unlikely to be matched by the anxiety your mother had, watching you wobble on a bike/motorbike/back of a boyfriend’s bike.

Bringing in care is often hard, very hard – it is for most people so don’t think it’s just you and your parent. You are asking the person to acknowledge they are no longer capable of looking after themselves. You see it as providing help, they don’t see it that way, they see you marking them as no longer competent. Look through their eyes.

Don’t confront, that never works, and it will damage your relationship with the person, just when you want the opposite. The trick to dealing with an elder is to stand beside them, not against them – they may have a very different perspective on the situation, and it’s their life that’s running out. They may be wrong, but as long as they’re safe and not a danger then that’s OK. (If you’ve ever had children you’ve been here before).

“My Mum wouldn’t let the carer we organised through the door (slightly embarrassing scenes at the front door). She had vascular dementia and just needed someone to check she was taking her meds and looking after herself. We then resorted to just a daily call from the carers but even then she started to avoid answering – which didn’t really help. The solution was to ensure neighbours were aware (of course they already were) and then wait. Eventually Mum got to the stage where she couldn’t cope and knew she couldn’t cope, so she had a carer popping in three times a day till she died. She was physically capable, but her mental capacity just gave up”.

Did I mention Grandy, my mother in law? Completely the opposite, she had severe mobility issues (veins again) so organised - on her own - a live-in carer, who was there for the last three years of her life. Stoic? She always said she wanted to donate her body to science (see below), the vascular problems meant she had toes removed one at a time so we joked she was supposed to donate her body all in one go, not bit by bit. Even though her body was ‘falling apart’ (her words) she was bright as a button and completely aware of everything till the day she just didn’t wake up. Not only had Grandy organised her own PoA when she was in her 60’s, but when she realised time was against her she stuck up a DNR notice on her kitchen window in case a doc or an ambulance was ever called (DNR – do not resuscitate). That’s planning for you.

Donating to science: often there will be a written request for the body to be donated to science, sometimes it’s just a spoken request. If this is the case, you need to start organising before the death – allocate the organising to one family member or executor. It’s may not be easy to find a hospital to take them, be prepared to spend time ringing around. Hospitals have capacity limits, and during winter many are full and won’t take any more. Plus, some have rules about not taking people who have died from diseases such as septicaemia in order to prevent any future infection.

‘When I organised my mother in law’s science wish it was in January and the big teaching hospitals were already full. None in the south would take her due to her chronic disease, others would only take her within three days of death…to the minute. She ended up going to Dundee but had to be there before five days were up – a mad overnight rush by a very helpful undertaker. I just rang hospitals and said, ‘My mother in law’s died, she wants her body to go to science, can you help?’. (Dundee’s medical school run the main European forensic pathology research unit - straight out of a Patricia Cornwell book).

How to write and read a eulogy

If you’re a boomer, you’ll have lived through the death of a direct family member- a parent, aunt, uncle, definitely grandparents. Eventually our parents will die, that’s simple physiology, you might outlive a partner.

Whether it’s a grand religious affair under a vaulted cathedral ceiling in Salisbury or under the branches of an oak tree in a Wolverhampton burial ground, people want to say ‘words’ as a last goodbye, as a last thank you. For an elderly person this should be a celebration of their life: it’s sad, but you know it’s the order of things.

You’re giving the eulogy to the audience, wherever you happen to be – and one last word to your parent/friend/relative/partner.

The audience is people who knew them, family friends, neighbours, fellow club members, but generally friends all.

To celebrate the person, you want to celebrate the life, so you can use that as the skeleton for the eulogy – tell the life story, tell people what they did, where they were when they were five, twenty five, forty five. What was life like for them back then? Was it wartime, post wartime?

Brainstorm ideas, gather all the key points and individual personal events from friends and family, ask for stories – they’ll be happy to be included in the process.

Read other eulogies and don’t be afraid to borrow lines that resonate with you, and that would have fitted in with the lost relative.

Introduce yourself and the other direct family members – the neighbours might not know who you are, and often they’ll want to speak to the family after with tales of memories and their loss.

Write out the eulogy longhand on paper; it’s a cathartic process and helps you to organise your memories and at the same to wash through the emotional pain involved with death of a close person. You’ll want to speak through the eulogy, and not be overcome (these notes came from groups of folk in America, they work).

A timeline is a great way of organising what you say – it automatically brings in places they lived, times and events they knew, places they went to school/university, places they worked, homes they had, holidays they took, and skills/hobbies/sports that threaded through their life. As you go through the timeline those events will resonate with the folk in the audience and bind them into the celebration.

The best eulogies have lots of stories, and relevant humour: that’s the way we tend to remember our nearest & dearest, we remember the happy times and the laughs.

Check the time allotted – it’s not a lecture, there’s more to tell about some than others, in general keeping towards 10/15 minutes or so should not upset the vicar!

Dealing with the emotion: if it’s a close parent/relative then even its after their 105th birthday the finality is upsetting. We’re human, we get upset and we cry when we’re very upset – it’s tough to deliver a eulogy when you’re stumbling with tears so here’s the exercise that’s tried and tested: the day or morning before, after you’ve written out the eulogy take it to the bottom of the garden, the loft, a locked bathroom, and read it out, deliver it to the tree/mirror/door in front of you. Read it through verbatim. When you’ve finished reading it out, start again. The American chums suggest reading it out loud six times – we agree. It flushes through the emotional stress, gets you all cried out so you can deliver a brilliant clear, fluent eulogy of celebration of which your Mum/Dad/Gran would have been proud.

No one ever teaches you how to write a eulogy, and generally you can’t ask your parents by the time you need to, so here are some examples to give you inspiration.

The Bookcase - a tale of Alzheimer’s

It was blustery and rainy on the Heath when my phone rang: my oldest sister with news that another of our sisters was about to be sectioned.

It started with a suggested diagnosis of early onset Alzheimer’s, distressing enough when your sister is only 6 years older than you, and progresses rapidly to a whole host of symptoms; trouble word finding, extreme forgetfulness, inability to focus on anything properly and a personality shift.

We kept her at home with a caring group of people around her, aware of the importance of stability and continuity. Two years later and she had become unable to stay in that environment. Her behaviour had become more erratic: burning her furniture in the front garden, trying to cut down live light fittings and most distressing of all losing her sense of self. The family realised a care home was the only option for our increasingly distressed and isolated sibling.

It took two attempts to find the right home that offered comfort and care on a one-to-one basis. The first home masqueraded as a dementia care home but in reality was part of a property portfolio for an American group of real estate investors. The second home had gentle staff who genuinely cared and created relationships with the residents. She settled in and after a few weeks of tears when we left she began to take to her two carers.

Then came the phone call, her behaviour had become increasingly erratic and violent and was so out of control she would need to be sectioned in a psychiatric unit of a hospital. Sectioning takes place to enable the medical establishment to assert their authority against an individual who is unable to make rational decisions about their own care.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest was my reference point, Jack Nicholson and others subjugated by a terrifying and brutal Nurse Ratched. A sea of Nurse Ratched’s controlling the narrative with drugs, cruelty, e.c. therapy or worse a total lobotomy.

I spent three nights in a state of high anxiety imagining her in the darkest place I may know with a host of other dementia patients, scrabbling to retain a small part of their personality and their dignity.

Dementia is not a disease of the dignified, and people appear to lose most of their identity whilst suffering from it. I was convinced that the sole purpose of sectioning was to strip away all the layers of personality and behaviour and leave the dried-out husk of a loved human being.

I paused at the door of the hospital accompanied by my other sister. I felt terrified and angry that her illness had come to this. I stepped inside feeling increasingly fragile.

The reality of the NHS and the staff could not have been more at odds with my fears. Smiling faces greeted us and introductions were made immediately. The anxiety slipped away almost imperceptibly, and I felt calmer than I had for days.

We had been invited to a meeting with nurses, a psychologist and other NHS staff to try to understand some of my sister’s behaviour and anxieties with certain people and specific situations.

The psychologist (born 1995) was gentle, approachable and demonstrated empathy and understanding that belied her age or experience. She likened memory in Dementia/Alzheimer’s to a bookcase, at the front the most recent memories, the middle shelf the adult years and at the back the childhood years. In dementia the bookcase falls over and the books get jumbled up leading to an unreliable time line or recollection of events. This in turn impacts on their emotions and behaviour. We found the analogy extremely powerful and very helpful in understanding the disease.

The meeting was highly emotive as a lot of the recollections that may have been buried emerged starkly in the fullness of the day. Though distressing it was cathartic and gave the group information to move forward with a comprehensive care plan and more ideas about different reasons for behaviour that my sister repeatedly displayed.

When I left having seen my sister, calmer, happier and seemingly more at peace, I felt her outward emotions wash over me.

The NHS was doing a remarkable job, they had had taken her from a destructive and very miserable place to somewhere more akin to her normal self. In time now that the medication and care plan is working she will be moved back to another care home. Everybody had her best interests at the core of their practice and she now seems to have a quality of life that she deserves and needs.

Thankfully no Nurse Ratched in sight.

Our readers’ favourite books

Over the last couple of months we’ve started asking a few simple questions when someone joins our Boomers’ Money Club: your favourite book; your first album; what’s top of your “bucket list”.

Here’s the list so far of our readers’ favourite books to help you discover some new ones. We’ll update it every now and then with newer responses.

1984 by George Orwell

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess

A Handful of Dust by Evelyn Waugh

A Prayer for Owen Meany by John Irving

A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khaled Hosseini

After the Flood by Kassandra Montag

Alchemy by Rory Sutherland

American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis

Atonement by Ian McEwan

Barbarossa by Alan Clark

The Big Short by Michael Lewis

Biggles by William Earl Johns

Birdsong by Sebastian Faulks

Bounce by Matthew Syed

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

Catch 22 by Joseph Heller and Howard Jacobson

Churchill by Andrew Roberts

Clear and Present Danger by Tom Clancy

Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons

Consider Phlebas by Iain M Banks

Cosmos by Carl Sagan and others

Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese

Days Without End by Sebastian Barry

Death and Destruction by Patricia Logan

Dog Man, A Tale of Two Kitties by Dav Pilkey

Dr No by Ian Fleming

Fatherland by Robert Harris

Five People You Meet In Heaven by Mitch Albom

Gambling Man by Lionel Barber

Gates of Fire by Steven Pressfield

Great Expectations by Charles Dickens

Helgoland by Carlo Rovelli

Hundreds and Thousands: The Journals of Emily Carr by Emily Carr

In the Blink of an Eye by Jo Callaghan

Just One Damned Thing After Another by Jodi Taylor

London: The Biography by Peter Ackroyd

Lord of the Rings by J R R Tolkein

Market Wizards by Jack D. Schwager

Middlemarch by George Elliot

Morality Play by Barry Unsworth

My Side of the Mountain by Jean Craighead George

Mr Nice by Howard Marks

Noughts and Crosses by Malorie Blackman

Outlive by Peter Attia and Bill Gifford

Parky by Michael Parkinson

Pegasus Bridge by Stephen E Ambrose

Perfume by Patrick Süskind

Precipice by Robert Harris

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Red Plenty by Francis Spufford

Riotous Assembly by Tom Sharpe

Ronan the Barbarian by James Bibby

Sum of All Fears by Tom Clancy

A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell

Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain

The Bee Sting by Paul Murray

The Crow Road by Iain Banks

The Cruel Sea by Nicholas Monsarrat

The Elephant Whisperer by Lawrence Anthony

The French Lieutenant’s Woman by John Fowles

The God Delusion by Richard Dawkins

The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

The Iliad by Homer

The Malayan Trilogy by Anthony Burgess

The Master and the Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

The Mediterranean Passion: Victorians and Edwardians in the South by John Pemble

The Old Man and The Sea by Ernest Hemingway

The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver

The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists by Robert Tressell

The Reader by Bernhard Schlink

The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafon

The Tailor of Panama by John le Carré

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy by John le Carré

Tunes of Glory by James Kennaway and Allan Massie

Ultra Processed People by Chris Van Tulleken

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalinithi

Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys

Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

Woolloomooloo by Louis Nowra

You Are Here by David Nicholls