The man from Boca

by Doug Brodie

/1. The anxiety we deal with

Anthony de Mello is a Jesuit priest:

"Think of yourself in a concert hall listening to the strains of the sweetest music when you suddenly remember that you forgot to lock your car. You are anxious about the car, you cannot walk out of the hall and you cannot enjoy the music. There you have a perfect image of life as it is lived by most human beings."

Imagine being made redundant, at the same being rendered unemployable, and having nothing but an account number holding an investment sum. Next month you are still unemployed, next year it’s the same position – no employment, no salary, just an investment account.

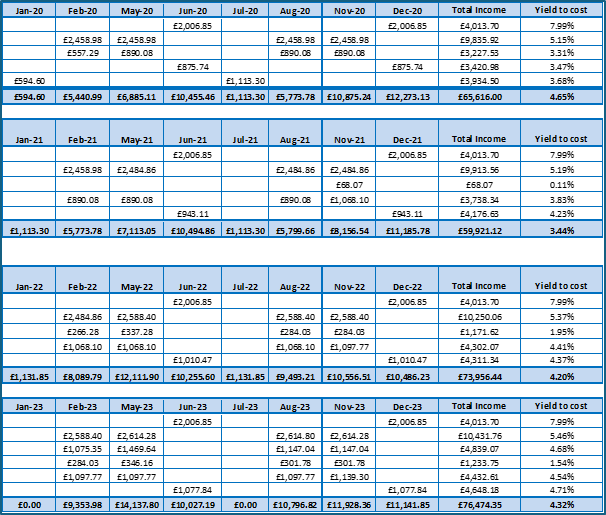

Our role is to do many things, however central to that is removing financial anxiety, and that is chiefly done by using predictable income that is visible and verifiable, and reconciling that month by month, year by year for clients. This is a redacted table of a client portfolio showing the monthly income (some columns hidden to be condensed). We believe all retirees with drawdown income should have similar projections and reconciliations.

/2. The most common pension mistakes made by DIY investors

DIY (“do-it-yourself”) investors managing their own pension income face a unique set of challenges. Without professional advice, it’s easy to slip up in areas that can erode your retirement savings or leave you exposed to risks. Here are some of the most common pension-income mistakes DIY investors make - and how to avoid them.

1. Underestimating Longevity Risk

Many retirees assume they’ll only need income for 15–20 years. In reality, a healthy 65-year-old may live another 20–30 years. Running out of money in your late 80s or 90s would be devastating. DIY investors often model their withdrawals on too short a horizon, leading to overly aggressive drawdowns early in retirement.

Tip: Plan for a long lifespan - use mortality tables or annuity quotes to stress-test your projections out to age 95 or 100. Use natural income and forget about it altogether.

2. Ignoring Sequence-of-Returns Risk

You’ll only do this once – the effects are devastating. Sequence risk arises when poor investment returns occur in consecutive years, forcing you to sell assets at depressed values to fund your income, and repeating the process in the following years without allowing your pension time to get back to par. Even if your portfolio averages 5% annual growth, a market crash in the first few years can deplete capital much faster. DIY retirees sometimes set a fixed withdrawal amount without a flexible mechanism to adjust during downturns.

Tip: Consider a “guardrail” approach—reduce withdrawals when markets fall and increase when they rise or hold a short-term cash buffer to cover 1-2 years of expenses. Use natural income and forget about it altogether.

3. Neglecting Inflation Protection

You will only discover this error about ten years down the line. Locking in a “safe” real-return strategy (e.g., 4% withdrawals from a portfolio) can leave you exposed if inflation spikes. Over decades, even modest inflation erodes purchasing power substantially. DIY investors may forget to include inflation-linked assets - like Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS), index-linked annuities, or real assets - especially in the early retirement years.

Tip: Allocate 20–30% of your portfolio to inflation-hedging investments and adjust your withdrawal rate annually in line with the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Or use investment trust portfolios and forget about it altogether.

4. Failing to Plan for Tax Efficiency

Different pension vehicles and withdrawal sources have varying tax treatments. Drawing entirely from a taxable account first, then a tax-deferred pension, can push you into higher tax brackets. Conversely, tapping tax-free accounts too early might forgo valuable tax-sheltering opportunities later on. DIY investors often overlook a coherent tax-efficient withdrawal sequence.

Tip: Map out your taxable, tax-deferred, and tax-free buckets. Use withdrawals strategically each year to stay within targeted marginal tax rates. Don’t forget that the state pension is 100% taxable.

5. Over-concentrating in One Asset Class

Home bias or “favourite” stock bets are common. Putting too much of your pension in a single company, sector, or region can expose you to idiosyncratic risk. DIY retirees sometimes forget to rebalance periodically, letting winners balloon into outsized portfolio weights.

Tip: Adopt a diversified core (e.g., a global equity-bond split) and rebalance at least annually to maintain your target allocation. Or use investment trust portfolios and forget about it altogether.

6. Relying Solely on Default Drawdown Solutions

Many platforms offer “glide-path” or “target-date” solutions that automatically shift allocations over time. While convenient, these cookie-cutter strategies may not align with your risk tolerance or income needs. DIY investors who “set and forget” these defaults can end up with overly conservative or aggressive portfolios at the wrong life stages.

Tip: Customize your glide-path based on your personal circumstances, and review it every 3–5 years (or after major lifestyle changes). Or use investment trust portfolios and forget about it altogether (they’ve been doing this for over 150 years).

7. Overlooking Estate and Legacy Planning

Failing to designate beneficiaries, or misunderstanding how pension assets are inherited, can lead to unintended outcomes: heirs facing large tax bills or assets being distributed contrary to your wishes. DIY retirees sometimes assume their pension will automatically follow a will - this isn’t always true.

Tip: Confirm beneficiary designations on all pension and investment accounts, and coordinate them with your will and LPAs.

8. Underestimating Costs and Charges

Pension platforms, funds, and investment products carry a range of fees - platform fees, fund management fees, transaction costs. Small differences in annual expense ratios (say, 0.2% vs. 0.8%) can compound to significant sums over a 20- or 30-year retirement. DIY investors often shop for convenience rather than cost efficiency.

· Tip: Regularly audit your total expense ratio (TER) across your portfolio, but never invest based on cost unless returns are irrelevant to you (which they’re not, given you’re reading this blog).

Conclusion

Managing your own pension income can give you control and possibly save on advisory fees—but it also introduces complexity and risk. By planning for a long lifespan, building flexibility into your withdrawals, diversifying, protecting against inflation and sequence risk, optimizing tax efficiency, and keeping costs low, you’ll set yourself up for a smoother retirement journey. Generally speaking, once you have given up earned income and you are entirely reliant of investment income, if you make a fundamental error, you are somewhat skewered – there will be a material financial cost to get things back on track, and an awful lot of anguish and anxiety in your household till it’s all fixed.

You most probably do not want to have money worries when you’re retired.

/3. Buffet: the fallacy of great fund managers.

As Buffett later highlighted in a celebrated 1984 speech, even relying on fund managers with an exemplary track record is often a fallacy. He imagined a national coin-flipping contest of 225 million Americans, all of whom would wager a dollar on guessing the outcome. Each day the losers drop out, and the stakes would then build up for the following morning.

Purely as a matter of statistics, after ten days there would be about 220,000 Americans who have correctly predicted ten flips in a row, making them over $1,000. Now this group will probably start getting a little puffed up about this, human nature being what it is. They may try to be modest, but at cocktail parties they will occasionally admit to attractive members of the opposite sex what their technique is, and what marvellous insights they bring to the field of flipping.

If the national coin-flipping championship continued, after another ten days 215 people would statistically have guessed twenty flips in a row, and turned $1 into more than $1mn. And still the net result would remain that $225mn would have been lost and $225mn would have been won.

However, at this stage the successful coin flippers would really begin to buy into their own hype, Buffett predicted: They will probably write books on ‘How I Turned a Dollar into a Million in Twenty Days Working Thirty Seconds a Morning,’ Worse still, they’ll probably start jetting around the country attending seminars on efficient coin-flipping and tackling sceptical professors with, “if it can’t be done, why are there 215 of us?”

Which is one reason of many why we focus on a single objective, which is manufacturing inflation-dealing income for life.

Do we beat the market? Ask the man from Boca ….

/4. When you probably do need an adviser.

1. At a life event such as a wedding, a birth, a death, an inheritance, divorce, or losing your income. The latter can be from being fired, walking out, redundancy, retirement or selling your business.

2. To hire skills and experience you don’t have: you can make a perfectly presentable dinner at home for family, but being able to tick the culinary boxes for strangers day after day after day is something you know you’ll need both training and practice to deliver. You can replace a waste trap on your sink but do you want to?

3. To delegate. Men happen to be particularly bad at this life skill, yet as age gradually reels us in it eventually happens to all. Plus, most folk would prefer their retirement to be about the Uffizi or tending a small vineyard in Crete rather than worrying over daily/hourly market news. Don’t forget about the admin - just because you’re doing it yourself doesn’t mean you shouldn’t account for the time or frustration involved.

4. Life change – inheritance, moving home, an illness or disability.

5. Specialist research – DIY investors are unlikely to have access to the contract, investment and comparison tools that are produced directly for the advisory community.

6. Second opinion: bouncing ideas of someone who works in the sector all day every day is at least going to confirm your current thoughts and actions. At the most it will stop you investing in the foreign exchange investment that has a 5% per month sure thing …

7. To ensure you can tell the difference between information and marketing – if you’re not paying for the online website or magazine you’re reading, then you’re the product.

/5. How to tell the difference between cost and value.

A bottle of Louis Roederer Cristal costs around £250. To a student, that is a whole month’s spending money, in City bars anything less would simply be, well… less.

There’s also the person in the pub (always a man?) who knows the price of everything: a mobile phone contract, an electricity supplier, even the difference between Tesco and Sainsbury. Unless you live almost next door to one I doubt your supermarket of choice is Aldi, even though you know it’s probably the cheapest option.

And if you’re ever ill, think food poisoning or similar - over indulgence at our age? - perish the thought! You know the phrase ‘my kingdom for a horse’. is the same as ‘anything you want to make me feel better now’.

So is £2,500 expensive? You don’t know, you can’t tell, because you only have the cost, you have no idea what you get in return, you have no reference point.

A 50 minute helicopter tour of London is £195. £2,500 is the price of 20 minute helicopter ride from Everest base camp back down to Kathmandu. Base camp is up at 17,598 feet, and generally takes 10 days of continual uphill hiking, living with Nepali food, Nepali hygiene, no running water, Nepali loos and an awful lot of dust. So, if on the edge of altitude sickness you throw in a dash of dysentery, and you’re laid up in your sleeping bag with no home comforts you might begin to contemplate the relative value of £2,500 for that 20-minute ride.

I didn’t, would you?