All things are possible

by Doug Brodie

/1. Of course you can, avoid retirement excuses.

This is the video of SJ Hall playing his Gibson 335 with the rest of his band.

And this is Zheng Tao swimming backstroke at the Paralympics, without any arms.

Now what do you think you can’t do?

There’s a guide on our website about behavioural biases, and we have a common mantra that the biggest danger to a retiree’s retirement portfolio is often that retiree. We are all genetically programmed to be cautious, to take care of ourselves, and rightly so when surrounded by fast cars, hot fires, electrical everything and water that looks fun to play in but… However, we do learn to master our fears, we work out how to resolve our pension income and in retirement we should take a leaf out of Eddie Izzard’s guide to life:

“Run towards what scares you [unless it’s a cliff]”

Eddie Izzard (Photo illustration by Salon/Getty Images)

And the call that came in just over 10 years ago was from a person earning £80,000 a year, in an executive role, who had saved £60,000 in his pension and wanted to know if that was enough to retire on, given he was already over 50. We’ll call him Gregor.

He did the right thing, he got it sorted, and he retired a couple of years ago. As they say, ‘the impossible we can do, miracles take a bit longer’. There is no sorcery or alchemy in retirement income: the final salary pension you or your friends may have is a promissory, legally binding income that is a liability on the employer. The employer will normally pay into that DB (defined benefit) pension pot over 20% of the salary, but the real value is that, irrespective of the capital accrued, the employer provides a guarantee that the pension will be paid, come what may, and that in itself is further underwritten by the Pension Protection Fund. But note, with an investment pension, none of that guarantee applies, and when you leave the employer, that’s it, in regard to their connection to your retirement welfare.

A large part of solving Gregor’s problem was running through the arithmetic, the compounding of returns and income, and how investments actually generate returns. Final salary schemes are run on the steady-eddy, predictable method of investing: we do exactly the same thing. First, we and Gregor picked a target – a year and an amount of income needed. Next, we worked back from there and calculated how much money he would have to contribute to his pot, given a rational, feasible investment return based on income.

“Everything was solved by working out how many shares of the different investment trusts he’d need to buy before he retired: we knew the income per share, so the maths was straightforward. Uncomfortable perhaps, complicated – no.”

/2. The banks are at it again, though slightly more disciplined this time.

This is not investing the way you and I do it; this is investment US and China style.

If you think an investment might go up 10%, then if you buy £1,000 and it does indeed do that, then at the end you have £1,100, which is a 10% return on your money.

Or you gear it; that simply means you borrow money at the same time, and you invest your money and the borrowed money together.

How gearing works: take the £1,000 you originally have in the example above and borrow another £1,000. You now have £2,000 to invest: the shares go up 10% and you now have £2,200.

At this stage you sell the investment and repay the £1,000 you borrowed.

You are now left with £200 profit and the original £1,000 you started with – you’ve made a 20% return on your money. You’ve doubled your profit whilst still only using £1,000 of your own money. Yes, you will have interest to pay on the borrowed money, but you get the gist of how it works.

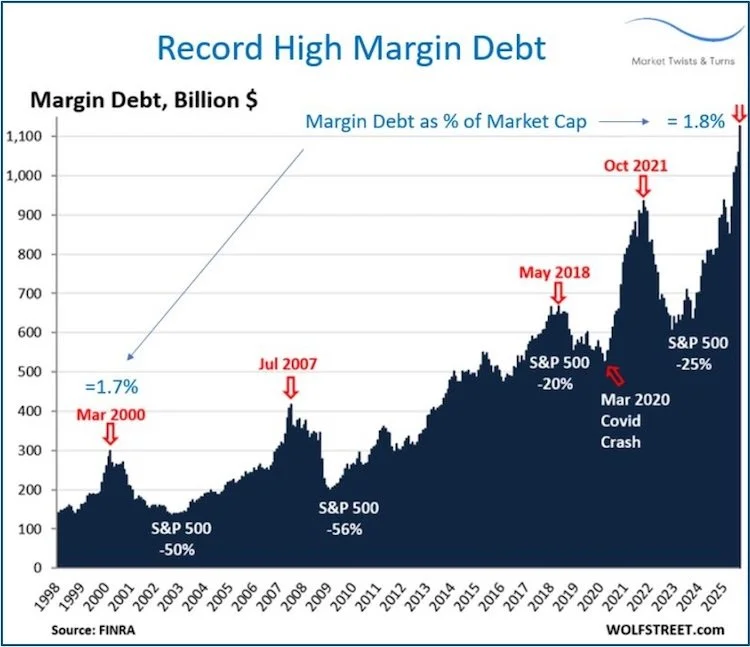

Now imagine you’re a hedge fund, or an investment bank, with $100’s of millions to invest. That’s what the chart above is showing us. It shows that at the peak of dotcom euphoria geared borrowings were equal to 1.7% of the US stockmarket. Now, it’s even higher, at 1.8% and with a much, much bigger stockmarket. The main difference is that the dotcom companies were very early stage, whereas the Mag 7 US firms are not – last year the generated roughly $411 billion of free cashflow.

“The Mag 7 generates more free cashflow than the entire GDP of South Africa, or Hong Kong or Colombia.”

Where do the investors borrow this money from? The banks and ‘private credit’ funds; the people in the banks create elaborate playbooks determining why the bank should make geared investments, the people then get their bonuses based on the amounts lent out, and if it all goes wrong the bank suffers the loss, not the employee.

Well they would complain, wouldn’t they? Privatise the profits, socialise the costs.

/3. Financial abuse is real: bullying or controlling, don’t get caught with this in a divorce.

A Quiet Professional Blind Spot: Financial Abuse and Our Responsibility

(This is an article that was previously posted by Claire McDermott in our trade press).

Financial abuse is rarely obvious, and that is precisely why professionals in our industry can unintentionally enable it.

In many households, particularly long-term heterosexual relationships, advisers default to dealing with “him”. He is often the higher earner, the confident communicator, the person who asks the questions. Over time, this becomes habit.

But habit is not neutrality.

The Australian authorities have a major outreach service making the issue transparent, and providing online chat, video or phone call support. They summarise financial abuse as:

It often involves someone using money in ways that can control and cause you harm. An example of financial abuse can include excluding you from important financial decision making.

When Convenience Becomes Complicity

In my own experience, an accountant allowed my self-assessment tax return and company accounts to be signed off by my husband, without any evidence that I had seen them, approved them, or even had access to them.

Only when the accountant later acknowledged that I was legally required to approve those documents, I suspect following some sort of audit, did something shift.

Suddenly, information that had been inaccessible became visible.

From the professional’s perspective, nothing malicious had occurred. From mine, it was transformative and allowed me to control the conversation around my finances.

“We just deal with him/her” isn’t harmless.

In financial services, phrases like:

“We usually deal with him/her”

“He/she handles the finances”

“She isn’t really interested in engaging”

…are common — and understandable.

But when money, assets, pensions, or investments are held in joint names, you do not work for one person.

Wealth managers and planners work for both. In general, all money is family money.

Failing to check consent, understanding, and access doesn’t just miss an opportunity to empower, it can actively reinforce an imbalance of power.

Why This Is Easy to Miss

Accountancy and financial services remain male-dominated professions. Many advisers are themselves higher earners, accustomed to control, and operating from a position of confidence and autonomy. After all, that’s their professional occupation, their experience, their qualifications.

That doesn’t make them abusive, but it does mean they are statistically more likely to identify with the controller rather than the controlled. Without conscious reflection, this creates blind spots.

Small Professional Actions Can Have Enormous Impact

The shift does not require radical policy changes. It requires intentional practice:

Ensure all named clients see and approve documents

Confirm understanding — not just signatures

Avoid defaulting to one partner as the decision-maker

Be alert to who speaks, who asks, and who defers

Remember that silence does not equal consent

Always ensure you have both email addresses and send correspondence to both. If you have one email address for both contacts, query it.

If the wife (and yes, it isn’t always the wife) isn’t engaging, reflect on your own practice, what adjustments could you make to ensure your services are accessible to everyone.

What feels like a minor administrative step to a professional can unlock autonomy for a client.

We are not suggesting all men who manage the finances are financially abusive

There are many couples where one person is happy for the other to take the lead on financial administration, and where access, transparency, and freedom are genuinely shared. Expecting couples to make every small financial decision jointly would simply add unnecessary life admin.

The question for us, as professionals, is different. It is whether we have a responsibility to notice when vulnerability may be present — and whether our processes are robust enough to identify and respond when that vulnerability is highlighted.

Financial Services Can Be Part of the Solution

Financial abuse, controlling or bullying thrives in opacity. Professionals are uniquely placed to interrupt that — gently, legally, and ethically.

This isn’t about policing relationships: it’s about remembering who your client is.

Sometimes, simply asking both people is enough to change everything. It’s polite, it’s professional and it’s the right thing to do.

“Above all else, involving both people in a couple in financial decision making, education and information is simply giving the correct personal respect to both parties.”

About the author

Doug is the Founder and CEO of Chancery Lane. He has worked with personal investing since 1989, specialising in income investing for the last fifteen years, firstly with Old Mutual and running his own award winning business since 1995. Doug is chartered with two professional institutes, CISI and CII, and certified by the Institute of Financial Planning.