The Cresta Run

by Doug Brodie

/1. Getting your pension right first time

Communication is not the swapping of words; it’s the attempt to transfer understanding. When we write, we know you probably don’t want a technical essay (our research is separate), and we know that it is what you can do in your retirement that’s the interesting part. It’s important for us that you and we have the same understanding about what we do: our aim is to have the pensions we manage as ‘boringly predictable’. Retirement is not about pensions, it’s about living with financial independence, being ‘of independent means’.

If you haven’t read any of the research papers yet, the white paper is in layperson’s language and it’s been described in the industry:

This is one of the most clearly written and compelling papers I have seen in a long time, especially for those managing their own SIPP and other investments for lifetime income planning.

If you haven’t, and if you’re able, then I’d easily recommend a trip to St. Moritz in the snow season. It’s the home of the Cresta Run and try it if you dare. It’s a 1.25km ice track, you slide down head first on something a little larger than a tea tray. Like your pension, it has to be right first time, as otherwise the bend known as shuttlecock will whip you out of that ice track with the 18kg sled following you. When you lie down at the start, you immediately slip down the ice slope. In the same way you can’t be a little bit pregnant, so you can’t be a little bit heading down the ice slope, nor can you be a little bit retired. Your pension and the Cresta Run are all or nothing, there can be no Plan B. That’s why you need to work with planners like us who are specialists, and who have been managing pensions for decades.

“Like the toboggan, your retirement time is sliding away, that time is getting shorter, not longer.”

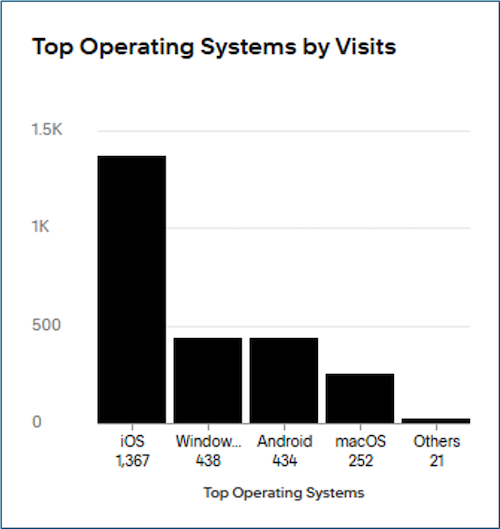

/2. Damn teenagers, always on their phone! (So are you, here’s the proof).

This is an analysis of how people reading last week’s newsletter did it, so if you’re on your iPhone, so are most others. This chart, and others similar, are why we have changed the format of our emails to you. It was pointed out by the lovely Claire that on a mobile, it was taking around 50 thumb scrolls for someone to read our long-form emails. So we looked at what our readers were doing and amended to suit everyone better. (Why are you lot all on your phone on a Saturday morning? That’s parkrun day!!).

/3. Everyone is normal – here’s a family story about money.

The lovely Claire I mentioned above? Here’s her story:

Class Roots (or: From Outside Toilets to Central Heating)

My childhood home came up for sale last week. Naturally, we were straight on Rightmove. You don’t not look. It’s practically a legal obligation. And there it was. The same house I grew up in. The house that held my entire childhood. The house that, somehow, now looks hollow and sad.

It made me think about class, chips on shoulders and money. And how wildly things change over generations – culturally, economically, emotionally – often without us really clocking it at the time.

A house full of love (and questionable wallpaper)

I grew up in a terraced council house. And I loved it. It was filled with love. And it was loved as a home.

My dad built the kitchen himself. We had a vegetable patch, a swing set, and swirly purple wallpaper that you could find eyes in if you looked hard enough. There was a black leather sofa – the height of sophistication – and low wire fences so you could lean over and chat to the neighbours.

We knew everyone. We lived opposite the playing fields and just around the corner from my nan and grandad. We had each other’s door keys. People were still Mr and Mrs Parry, and Miss Marion. We didn’t shout across WhatsApp – we shouted across the fence.

There was no central heating. We had Crittall windows. It was freezing. We used to get dressed at the bottom of the stairs in front of a gas fire because that was the only warm bit of the house. We made mud pies in the garden. My dad kept his car in a block of garages down the road.

It wasn’t fancy. But it was safe, warm (ish), and happy.

What it looks like now

When we looked at it last week, I barely recognised it – not because it had changed, but because it hadn’t.

The kitchen my dad fitted over 40 years ago was still there. Everything else felt tired. Sad. Like all the love had quietly drained away over time. The estate itself has changed too. It’s now the kind of place people live if they have no choice. That wasn’t how it felt then.

Back in the day, everyone worked for the same big local employers. People had moved out of London for work, put down roots, started families. Extended families lived nearby. There was grass. There was pride. There was community.

Further back than we like to admit

Go back another generation and one half of my family worked in service – staff in big houses. The other half worked in factories.

My dad left school at 15. He was bright, artistic, and curious, but that’s just what you did. He grew up in a village cottage with no electricity, an outside toilet, coal fires, and a bath kept under the kitchen worktop, filled once a week for everyone to use in turn. He had an adventurous, thoroughly feral childhood – running wild in fields and fairways, coming home filthy and happy. He had, and still has, a country accent.

Mum and dad met on a blind date and soon married. My dad had big collars, winkle-pickers and huge sideburns. Mum was beautiful with tiny mini-skirts and freckles.

My mum grew up on the outskirts of London, then moved further out when her parents followed work. She worked as a typist until she got pregnant with me, at which point she left – because that’s what women did then. She always had an east-London/Essex accent.

Council houses were respectable

Our council house wasn’t just a council house. It was the council house. The same one my grandparents had lived in. The one my mum grew up in. We knew everyone because we’d always known everyone.

When my parents were given the option to buy it, they did. Then interest rates went through the roof. I didn’t know it at the time, but we were inches from losing our home, and mum took on an extra part time job stacking shelves to help keep us afloat.

Childhood, however, remained blissfully ignorant. We went camping. We drove through central London with a tent in a trailer – this was before the M25 existed. We were the first people we knew to have a telephone installed. A beige one. With a curly wire. Attached to the wall in the kitchen. No idea why. We weren’t flash. We just… had a phone but didn't know anyone else with one to call. We went out for the day, all bundled into my auntie's mini. No seatbelts obviously - my cousins and I used to turn around and see how many drivers we could get to wave at us.

Quiet ambition, loud pride

My parents were very working class. But they were also quietly ambitious – for us.

I passed my 11+ and went to grammar school. Two of us passed from our primary school. Me, and a boy called Ralph. No tutoring. You just turned up and hoped for the best. At grammar school, I was one of only two girls in the whole year who hadn’t been to private school. I’d never played netball. I didn’t know long division. I stuck out like a sore thumb.

There was a school trip to Florence. My parents couldn’t afford it. The school suggested I apply for a grant. I was interviewed by a panel. One woman – impeccably posh – asked why my parents couldn’t afford to send me. Did they drink? Did they smoke? Bloody cheek. I still remember her, and not fondly.

But my mum and dad? They were so proud. I went on to university – the first in our family. Back when there were no fees and you got a grant. Imagine that.

Three generations later

My mum introduced me to the man who is now my husband. He’d been to university too. We were the first to live together before marriage. We moved to London. Got “professional jobs”. A mortgage. Eventually moved to a grown up sensible town. We lost our accents and became terribly neutral (although mine reverts the second I get over the Dartford Crossing).

We had children, both at/went to grammar school, university is a given.

We both have careers. I run my own company and have been to 10 Downing Street. We have two cars. Foreign holidays. Pensions. Insurance. Four mobile phones. Central heating. Bedrooms you can get dressed in without risking hypothermia. The phone with the curly wire is long gone. In fact, the home phone itself is now obsolete. In just three generations, we’ve gone from being servants, maids and working in factories, shared bedrooms, outside toilets, and no electricity… to this.

The uncomfortable question: but are we happier?

All this change. Life is more comfortable and we're happy. But are we any happier?

What will life look like three generations from now? What will our great grandchildren be doing if Trump and Putin haven't blown us all up by then?

That’s the lens we bring to retirement planning because money isn’t just numbers on a spreadsheet. It’s history. It’s security. It’s fear. It’s pride. It’s not wanting your kids to worry like you once did – or like you never even realised you were worrying. We don’t come at retirement from ivory towers or inherited wealth. We come at it from lived experience. From council houses, curly-wired phones, and parents who quietly grafted so the next generation could have more choice.

The Ashby-Hawkins family go back in time with presenter Giles Coren. Photograph: Duncan Stingemore/BBC/Wall to Wall

And maybe – just maybe – a bit more warmth upstairs?

About the author

Doug is the Founder and CEO of Chancery Lane. He has worked with personal investing since 1989, specialising in income investing for the last fifteen years, firstly with Old Mutual and running his own award winning business since 1995. Doug is chartered with two professional institutes, CISI and CII, and certified by the Institute of Financial Planning.