Don’t get fooled again

by Doug Brodie

/1. Don’t get fooled again

Private credit is simply shadow banking, and shadow banking is providing loans like a bank when you’re not a bank. It’s a mechanism for corporates to raise debt, and that is precisely what is going wrong in the US just now, with three very large companies going bust, having grown their businesses with debt.

This is how one of the clever people has summarised how part of this debt arranging has been taking place. Essentially in the UK, we know this as invoice factoring – this is where you issue an invoice to a customer, and while you wait to get paid, you ‘sell’ the invoice to lender for immediate cash, say at 70p in the £. This gives you immediate cashflow, cash in your bank, to use as needed.

Basically, the diagram is showing that the invoices (receivables) are sold on to a ‘special purpose’ vehicle/company that then packages all those receivables and sells blocks of that debt to investors (the creditors).

What could possibly go wrong? The sums involved are huge – reports suggest that the total outstanding in factored invoices in the US by 2024 was $4 trillion. Some time someone somewhere is going to have to pay cash for their bill otherwise the whole thing crumbles; human nature says it will. This is similar to the fundamental cause of 2008, however this time it is not with banks, it is with private credit funds – so if your pension fund manager starts suggesting a good diversification using private credit, just say no. Apart from the fundamentals, if it was such a good deal Goldman Sachs wouldn’t let it out their door.

Heads we win, tails you lose.

The venerable Jason Zweig writes for the Wall Street Journal and recently wrote up an example of the fast practice within private equity that the retail investor never sees, and which the institutional investor, including pension funds like yours, choose at times to ignore.

This is a summary of his analysis of a private equity fund called Hamilton Lane, a $3.6 billion fund (that’s an awful lot of other people’s money):

Summary: How a Private Equity Fund Changed Its Fee Rules

What This Fund Does: Hamilton Lane runs a $3.6 billion investment fund that buys stakes in private equity investments from other investors who want to sell. Think of it like buying used luxury goods - sometimes people need to sell quickly and accept less than full price.

The controversial practice: here's where it gets interesting. When Hamilton Lane buys these investments at a distressed discount (say, for 89 cents on the dollar), they immediately record them on their books at nominal full value ($1.00). This instant "markup" makes the fund look incredibly profitable - sometimes showing gains of 1,000% in a single day. While legal, critics call this "NAV squeezing" (NAV = Net Asset Value, basically what something is supposedly worth).

The Fee Structure Change. Originally, Hamilton Lane could only collect bonus fees (12.5% of profits) when they actually sold investments for real profits. Since they rarely sell, they collected almost no bonus fees despite showing huge paper gains.

In March 2024, shareholders approved new rules:

Bonus fees dropped to 10% (from 12.5%)

BUT now Hamilton Lane can collect fees on paper profits, not just actual sales.

This immediately netted them $58 million in fees they couldn't have collected before.

“They turned paper profits into $58 million cash bonuses.”

Why This Matters: critics suggest Hamilton Lane rushed to grab these fees because they might suspect the paper gains won't materialize as real profits later. It's like an estate agent taking commission based on their own estimate of your house's value, rather than waiting for an actual sale.

There are myriad issues here, not least that such funds are not supervised by the regulator on a retail basis because they are deemed to be ‘beyond the ken’ of retail investors, though I’d think few institutional investors are up to speed on this. You might think your house is worth £2 million, but the real price is what you receive, not what you’d like to think.

/2. Can you name this?

I never knew, I’d never seen one before though you and I have talked about them quite a few times.

(If you get stuck, email me).

/3. UK – what Reeves is blatantly avoiding discussing.

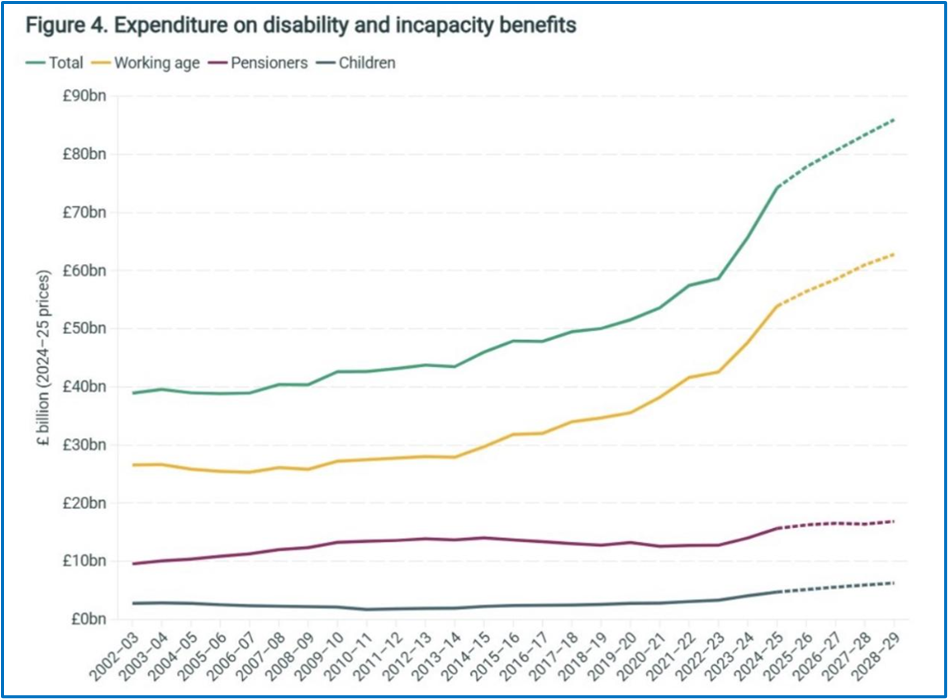

These charts are from our chums at JP Morgan; it’s interesting to note that the current Chancellor is keeping the rumour mill running on talk of tax, and nothing about the core issues.

She seems to have forgotten about Mr Micawber’s rule of basic housekeeping and “a budget is about telling your money where to go, not wondering where it went”.

Interestingly something clearly changed in 2022-23, and also, the problem with disability issues is not with pensioners, it’s with working age people.

Irrespective of tax rises, the top chart showing the forecast rise in government spending is clearly the issue; difficult decisions need to be made. That’s their job.

/4. If you think you know better than Buffett

In the late 90’s tech stocks took off, the internet was arriving, and people thought the companies involved would keep racing higher for ever. This was when Sun Microsystems CEO, Scott McNealy, famously berated investors with:

“At 10 times revenues, to give you a 10-year payback, I have to pay you 100% of revenues for 10 straight years in dividends. That assumes I can get that by my shareholders. That assumes I have zero cost of goods sold, which is very hard for a computer company. That assumes zero expenses, which is really hard with 39,000 employees. That assumes I pay no taxes, which is very hard. And that assumes you pay no taxes on your dividends, which is kind of illegal.

And that assumes with zero R&D for the next 10 years, I can maintain the current revenue run rate. Now, having done that, would any of you like to buy my stock at $64? Do you realize how ridiculous those basic assumptions are? You don’t need any transparency. You don’t need any footnotes. What were you thinking?”

To put today into perspective, Nvidia is valued at 27 years revenue. The MAG 7 in aggregate is 7.8.

At that time Warren Buffett sat back and didn’t play, boy was he castigated for doing so, and his performance suffered as the tech values took off. The following years were clearly different and that’s part of the reason for Berkshire Hathaway’s success. With their cash they were also able to bail out Goldman Sachs in 2008, charging them 10% per annum, which was $1,400,000 per day. (Bet that hurt the squids).

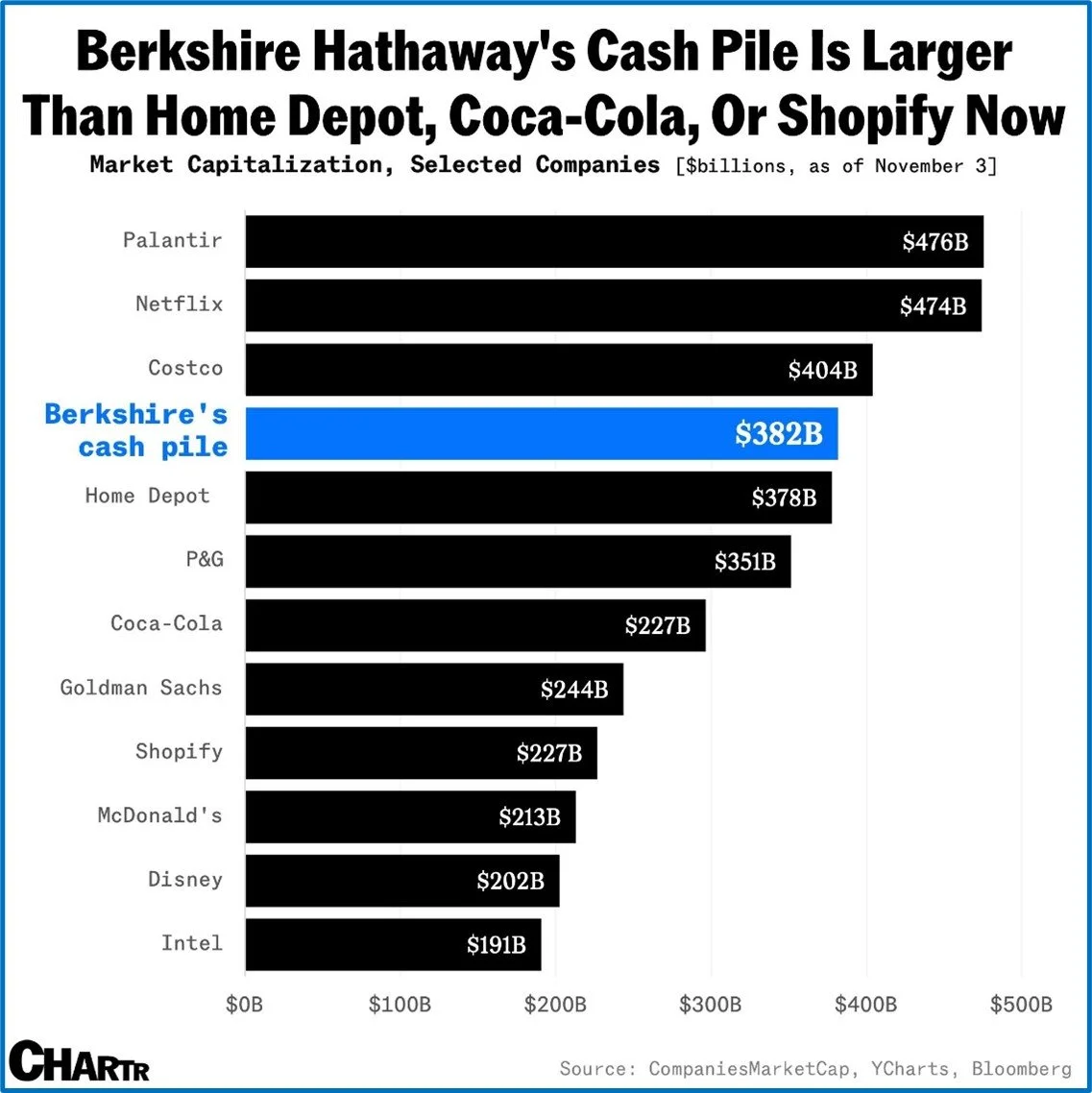

He’s doing it again; this time he’s taken their cash up to $382 billion:

It’s easy to get number blindness seeing so many figures splashed across the media every day (Ed: and this blog, Doug!). So, here’s some reference points for that cash pile:

If you want to be sure of catching a bus you get there early, so even if lots of people show up you know you’ll stand the best chance of getting on board. With the amount of money they control Berkshire Hathaway has to be early – they don’t need to finesse valuations because they can move whole markets with their ammunition. One wonders who they will swallow when the tide goes out and some big names are caught short and desperate?