Just how bad can your provider be?

by Doug Brodie

/1. Just how bad can your provider be?

1. Our biggest clients came from UBS in 2008 and 2009; during the credit crunch the bank itself came under a sticky amount of pressure trying to stay afloat, so simply refused to work with retail clients whose own money was stuck. Next, at the beginning of this year the bank’s clients lost money on a foreign exchange derivative position they had been sold, following the Tariff Tantrum. According to the FT “one client lost more than SF3mn, and a second lost 15% of their assets. “I repeatedly expressed concerns about the product and said I did not understand it. They kept telling me not to worry…”

2. Pension companies are getting bought and merged, and that process has been going on for around twenty years, mainly caused by those running all the big Scottish houses getting their sums completely wrong, and a Canute-ian refusal to acknowledge market changes. Outside work, I joined a friend as he called his late father’s pension provider to try and sort out probate. It became obvious to me the pension person was quite clueless so after some questioning the person on the end of the phone admitted he didn’t work for the pension company, he worked for an outsourced call centre, and that he could only read from the scripts provided on the screen. Even better, his afternoon shift was handling call work for a garden centre.

3. Eventually one of the nation’s high street banks reckoned that instead of selling a pension company’s products it should just buy pension companies; it has now bought so many, and dutifully got rid of all the staff, that it has removed all phone numbers from all the websites and will only communicate by email or letter. We started client A’s transfer at the beginning of December 2024, it completed nine months later.

4. Client T asked for a withdrawal of some money from his investment bond. We arranged the sale to cash that morning and submitted the withdrawal request. When chased a week later this subsidiary of a $25 billion corporation told us ‘Sorry, there’s a 42-day turnaround’. That’s 42 working days, so over five weeks. Fortunately, we were able to track down the CEO of the UK firm and resolved that matter after a few days (it’s part of what we’re paid for).

(Couldn’t resist).

/2. Even God can’t beat pound/cost averaging.

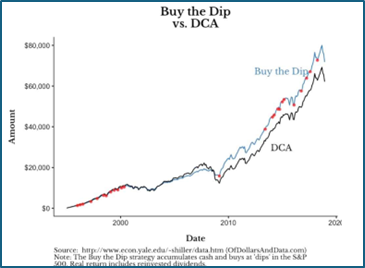

There’s a firm in New York called Ritholtz Wealth who we like; they write well and publish a lot of research, a strategy we like to follow. This article was published by its COO Nick Maggiulli in 2019: it starts “This is the last article you will ever need to read on market timing”.

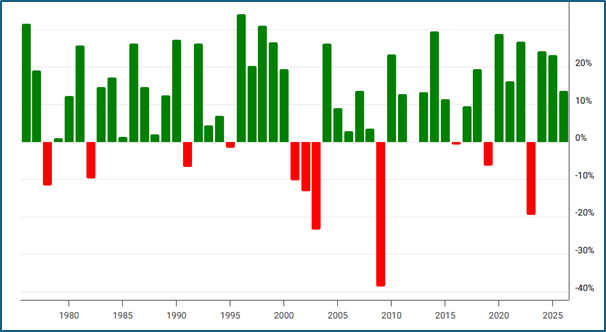

This is the S&P 500 – over the last 50 years there has been 11 negative years, or 22%.

The Simple Truth About Trying to Time the Stock Market

Let me tell you something that might save you a lot of headaches: trying to time the stock market probably isn't worth your effort. Here's why.

A Thought Experiment

Picture this: You're transported back to sometime between 1920 and 1979, and you need to invest in stocks for the next 40 years. You get to choose between two approaches (this is from New York hence it’s in US$):

Option 1 - The Steady Approach: Invest $100 every single month, no matter what's happening in the market.

Option 2 - The "Smart" Approach: Save up $100 each month and only buy when stocks are on sale (when prices have dropped).

And here's the kicker - I'm giving you superpowers. You'll know exactly when the market hits rock bottom before it goes back up. You'll always buy at the absolute lowest price possible.

Which would you pick? Option 2 seems like a no-brainer, right?

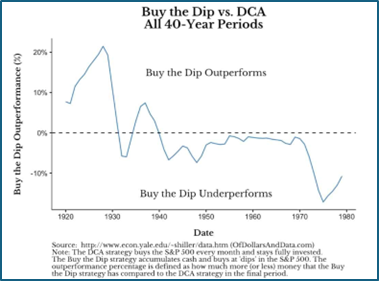

Here's the surprise: The "wait and buy the dip" strategy loses more than 70% of the time, even with perfect knowledge of when to buy.

Why Does This Happen?

The problem is simple: Big market crashes don't happen very often. Throughout American history, we've really only had a few devastating drops - the Great Depression in the 1930s, the rough 1970s, and the 2000s. Most of the time, the market just keeps climbing higher.

So while you're sitting on your pile of cash waiting for the perfect moment to buy, the market keeps going up without you. You're missing out on growth month after month, year after year.

Real-world example: Imagine your colleague Eloise started saving $500 a month in January 2010, waiting for the "next big crash" to invest it all at once. Meanwhile, her mate Isaac invested his $500 every single month. By 2020, Eloise had $60,000 sitting in cash earning almost nothing, still waiting for her perfect moment. Isaac, who just bought steadily, saw his investments grow to over $100,000 because he was in the market during one of the longest bull runs in history.

A Real Example from History

Let's look at 1995 to 2018. During this time, the "buy the dip" strategy worked pretty well because there was a massive crash in 2009. If you had bought at the absolute bottom in March 2009, every $100 you invested would have grown to about $350 by 2018. Tidy.

But here's the thing: You would have been sitting in cash for nearly 9 years waiting for that moment, while the regular "invest every month" approach was buying stocks the whole time and benefiting from their growth.

To put this in perspective: Let's say you started with $10,000 in early 2000. If you invested it all immediately, even though you'd go through the 2000-2002 dot-com crash and the 2008 financial crisis, by 2018 you'd have roughly $26,000. But if you held that $10,000 in cash waiting for the "perfect" moment and only invested at the March 2009 bottom, you'd have about $32,000. Sounds better? But here's what you gave up: nearly a decade of stress, constant checking of the news, and the very real risk that you might have chickened out or missed your timing by even a few months.

The Worst-Case Scenario

Now imagine starting your investment journey in 1975. The next big market high doesn't happen until 1985 - that's 10 years of waiting! During that entire decade, you'd be holding cash while prices slowly climbed. By the time you finally got your "dip" to buy, the steady investor had already been in the market for years, making money.

Here's what this looked like in dollars: Someone who invested $100 monthly starting in 1975 would have put in $48,000 by 2015 (40 years later) and ended up with around $400,000. Someone trying to "buy the dip" with perfect timing during this same period? They'd end up with only about $300,000 - $100,000 less, despite knowing exactly when to buy!

The Great Depression: When Timing Actually Worked

There's one famous exception that proves the rule. If you started investing in 1928 and had perfect timing to buy at the absolute bottom of the Great Depression in June 1932, you'd have done incredibly well. Every $100 invested at that bottom would have grown to $4,000 by 1957.

But here's the reality check: To actually pull this off, you would have needed to watch the stock market lose nearly 90% of its value from 1929 to 1932, witness banks failing, see people losing their homes, survive the worst economic catastrophe in modern history, and then confidently invest everything in June 1932 when everyone around you thought the world was ending. Could you really do that? Most people who lived through it couldn't either - they were too scared, broke, or both.

The Real Kicker

Remember, all of this assumes you have perfect timing - that you somehow know exactly when the market hits bottom. In reality, nobody has this ability. When I tested what happens if you miss the bottom by just two months (which would actually be incredibly good timing in real life), the "buy the dip" strategy loses 97% of the time. Basically, you're almost guaranteed to do worse than just investing regularly.

Here's a modern example: Remember March 2020 when COVID hit? The market bottomed on March 23, 2020. Let's say you were waiting to buy the dip. Did you know on March 23rd that was the bottom? Of course not! Most experts were predicting things would get much worse. If you waited just until late April to be "safe," you missed a 30% gain. If you waited until summer when things "felt better," you missed a 50% gain. Meanwhile, someone who just kept investing through it all captured all those gains without the stress.

What This Means for You

If you have money to invest, you're almost always better off just investing it now rather than waiting for a better price. That "perfect moment" might never come, or it might come so far in the future that you'll have missed years of growth.

Your friend who keeps saying they're "waiting for the market to drop before buying in"? They're probably making a mistake. While they wait, they're missing out on the power of compound growth - where your money makes money, and then that money makes even more money.

Simple example: Let's say you inherit $10,000. You could:

Invest it today at regular market prices, or

Wait for a 20% crash to get a "deal"

If you invest today and the market grows at its historical average of about 10% per year, in 10 years you'd have roughly $26,000. Now let's say you're lucky and a 20% crash happens next year. You buy in then at "20% off," and then the market grows at 10% annually for the next 9 years. You'd end up with about $23,000. You got your crash and still ended up with $3,000 less because you missed a year of growth!

The Luck Factor

One of the most sobering findings: your success in investing depends heavily on when you happen to be born and investing - something completely out of your control.

For example:

If you invested $48,000 over 40 years starting in 1922, you'd end up with over $500,000

If you invested the same $48,000 over 40 years starting in 1942, you'd only end up with $153,000

That's more than three times difference, just because of when you were born! This difference (226%) is way bigger than any benefit you might get from perfect market timing (which tops out around 20% improvement).

The Bottom Line

The stock market generally goes up over time. Yes, there are scary drops along the way, but they're unpredictable. Even if you had a crystal ball and knew exactly when those drops would happen, you'd still probably do better by just investing steadily month after month.

Think of it like this: Trying to time the market is like standing at a bus stop with money for a ticket, but refusing to get on the bus because you're waiting for one that's less crowded. Meanwhile, buses keep leaving - some full, some empty - but you're still standing there. Your friend who just got on the first bus? They're already halfway to their destination. More, you don’t know if the one in front of you is the least crowded until it has left.

You don’t know when the dip bottoms until AFTER it has passed simply because it is ‘bottom’ with reference to the price of the market both before and after. Picking the bottom, in a single purchase, is therefore pure luck.

Nick Maggiulli then re-ran the data on a realistic basis, meaning timing the purchases two months after the actual bottom – in doing so missing the bottom by those two months meant underperforming dollar/pound cost averaging 97% pf the time.

/3. “We should never be so old as merely to watch games instead of playing them”.

Put two or more actuaries together in a room and before long you’ll hear them talking about longevity – how long will you live?

We do a huge amount of research into our data to determine income sources for our clients that will last a lifetime – your lifetime. It’s all a bit of a waste of time if your daily diet starts with Nigella’s fried brie, parma ham and fig sandwich, which she indelicately fries in butter, and then a little more butter.

Our work is as a retirement enabler, so now we rely on you to use that time being happy and mens sana in corpore sano. (School day tip: that is also written as ‘anime sana, meaning ‘soul’ instead of ‘mind’, and the running brand ASICS is the acronym of that phrase).