The simple maths behind returns

by Doug Brodie

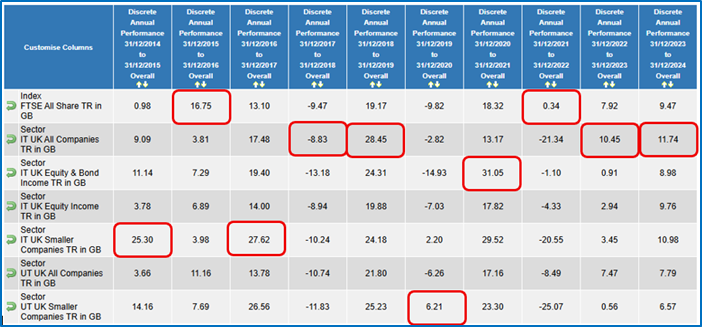

/1. 10 year discrete returns – the FTSE index vs the active sectors, can you spot a trend?

This is the investment returns for the FTSE All Share (top line) compared to the sectors of the actively managed funds; “IT” is investment trusts, so the label ‘IT UK All Companies’ means all the investment trusts that invest across all UK listed companies.

Two things stick out in this table: for 80% of the time measured the index was beaten by active managers, and for 70% of the time investment trusts in the broad UK all companies and smaller companies sectors outperformed unit trusts. We have to research unit trusts, pension funds and ETFs to ascertain which investment structure tends to do best; we are investment agnostic, our task is wonderfully broad in directing us to simply hunt for the best.

Best is the enemy of good.

What we know: the market will go up and down randomly, from year to year and minute to minute.

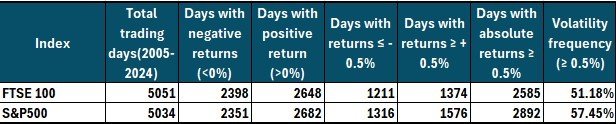

Over the past ten years there have been 5,051 trading days in the UK, and of those days, 51% of the time the market moved up or down over 0.5%. There were 2,398 negative days, so 47.5% of the time investors lost money.

What we know: the markets everywhere will have frequent down years. This is the broadest of the broad markets, it is the MSCI World index:

This is the maths behind a key part of our strategy (and Roger Federer’s):

If an investment falls from 100 to 80, that is a 20% fall.

To get back to 100 the investment of 80 now has to grow by 20, which is a 25% increase.

If an investor has a cautious investment that only falls by 10 from 100 to 90, that 90 only has to grow by 10 to get back to 100, which is an 11% increase.

Increases of 11% are much quicker and more frequent than increases of 25%.

Charley Ellis wrote the book years ago – he ran his own firm, Greenwich Associates, and was a director at Vanguard.

/2. Retiring – what you’re supposed to be doing.

Something to watch if you’re a boomer.

You’ll probably know Frances McDormand and Joel Coen; they produced a documentary called The Bend in the River, best explained here, by Variety:

“The film is the final instalment of director Robb Moss’s doc trilogy about a group of free-spirited friends navigating their way through life. (Think Michael Apted’s “7-Up” docuseries.) Moss, a veteran documentary filmmaker and a Harvard professor, began filming the group of five friends in 1978, when they worked as river guides in Colorado. The twenty-something friends and their trip down the Colorado River became the subject of the 1982 doc:” RiverDogs.” Moss followed that up with the 2003 doc “The Same River Twice,” which follows the same group of friends as they come to terms with the complex realities of adulthood.

“The Bend in the River” weaves new footage of the group with old footage from their youth. Now in their sixties, the film captures the group who have held jobs, been married, had children, seen those children married, divorced, remarried, helped raise grandchildren, dreamt, suffered, succeeded, and survived.

“Filming five friends intimately for nearly fifty years gave me the chance to closely observe the action of time in the lives and bodies of my friends and, of course, in my own life and body as well,” says Moss. “While our aging carries “The Bend in the River” forward, it is the stitching together of the forgotten moments of our lives that animates the film. Life is not orderly — our desire to make and re-make memories often disorders things even as we grasp for meaning. What does it mean to live a life? What is the relationship between the past and the present? How does who we were affect who we’ve become? The film was an opportunity to drench my friends in time and create a five-person cinematic mosaic, whose shape and purpose emerge over time.”

When the documentary gets to boomer time, the four have all ended up in entirely different lives, lifestyles and places. Now’s the time to ask them to consider the decisions they made and if they’d do the same again, and how they feel about what the future now holds, shaped by their previous decisions.

Retirement is a real crossroads, several routes to take (including still being at work) – there’s no downside to listening to your peer group’s experiences, and it might just help affirm your thoughts about what’s important.

It’s hard to find streamed, I’ve written to the production company asking if we can purchase it on DVD.

/3. What was born in 1960, costs £2.3m and you use it to thrash around a race track?

“Lady luck sure smiled on me”. Marvin Gaye, 1964.

Most of us have achieved a level of wealth that almost all of human kind could only dream of. Most of it is luck. Lucky to be born, lucky to be a citizen of the UK, to have free education available and drinking water piped into our very own houses.

If your wealth today is from a lifetime of employment, someone else started that company and went through the hard yards. You were lucky to be able to join something that had been built; if it was in finance then you’re lucky to live in a country where there is so much capital over and above daily living expenses that whole industries have been created by that excess capital.

This is an Aston Martin DB4 GT :

It was sold in 2018 for between £2.3m and £2.5m: a lucky person had sufficient spare capital to spend it on a car that’s no good for popping down to Tesco.

I know this car: my client at the time was the son of a WWII Spitfire pilot who fought in the Battle of Britain. His life had always been around cars, and this Aston was bought by a friend of his. They were both lucky: the friend has enough spare capital to buy it, and my client was lucky to be asked to race it.

Race it??

Apparently it was dented, smacked, bent frequently and I was told that the real value lay in the originality of these two badges:

/4. Lucky – this is you and me.

How lucky to have sufficient spare capital to buy such a wonderful car, and then to afford to race it – most people would be paranoid about taking it out on a rainy day never mind thrash it around the Spa race track for six hours non-stop with 70 other cars hammering to get past.

You have to be lucky to have been born in the UK, brought up with more effective medicines than King George V had, and you and I have something that Andrew Carnegie would have given his entire for – being alive today.

Carnegie was the richest man in the US in 1900, chiefly through steel and railways.

He have away $350 million before he died ($6.9 billion today), and after his death the last $30 million was given to foundations, charities and pensioners.

We come into this world with nothing, we leave with nothing – in between luck plays a big part! Be reassured you’ll be as wealthy as Elon Musk when you’re both dead.

Lucky is probably also that when we were kids and our bike broke, we just knocked on a neighbour’s door to help. We lived with patience, and we waited for letters to arrive. We wrote letters. We waited for our favourite songs to be played on the radio and for the next episode on TV to be played next week.

And this is a summary of our luck: “My name’s Richard. I’m 74”

“Everything changed in our time – we are lucky to have feet in both worlds: we have learned first to type, then to swipe. We saw the first cash point (Barclays) and we now no longer need money because we can just tap, and we can send money overseas in seconds. We have followed maps and we have followed sat navs – bored waiting in carsm, we’ve read the A-Z. (Dad, what’s an A-Z?). We can plant tomoatoes and send emails, we’ve buried friends and parents and welcomed grandchildren. Every generation builds the road a little further, however, ours remembers both the unpaved roads and the 6 lane lane highways. We’ve been lucky to have experienced such huge changes for the positive.”