Trust in meeee

by Doug Brodie

/1. Can you play tennis?

Rose Blumkin was one of Mr Buffett’s favourite business people, he bought Nebraska Furniture Mart from her, a business she had started with literally hot air and chutzpah:

“If you want to sell her 2,300 end tables,” he said, “she will know in a minute what she can pay, how fast she can move them, the whole thing — and she will buy them from you. She’ll wait until just before your plane is going to leave in some blizzard when you have to get the hell out of Omaha and can’t afford to miss your flight [in order to drive the hardest bargain].”

“She will know exactly what she can do with [the end tables] and exactly what price she needs to pay — and she won’t be wrong.”

But bring her something even one inch outside her circle and she won’t even give it a second glance. No temptation and no ego-driven detour into parts unknown. “That is a smart woman,” said Buffett. “And that is why she has killed everybody else.”

I’m sure you can play tennis, however, you can’t play pro tennis, there’s a difference. We don’t run emerging markets portfolios because we don’t know enough to make the decisions ourselves, and we’re willing to pass on to others all the things that we can’t evaluate. Like pro tennis, there are lots of things we can’t do, and knowing those limitations enables us to ruthlessly draw our circles of competence – it’s money after all, and it’s our clients’ money. Some DIY-investors are really good, however, the £3.4 billion in Woodford funds via Hargreaves Lansdown suggests most are not – for one, most DIY investors have no training in retail investment analysis, secondly, DIY investors invest with no accountability except to themselves, they have no critics and so suffer terribly with confirmation bias.

/2. How does a trust work, is it that simple and what’s the difference between the ‘majors’?

Beware the ‘bare’ – like an annuity, it’s simple but there’s no going back.

A bare trust is the simplest form of trust. The beneficiaries are fixed and absolutely entitled to both the income and capital from the start. Trustees hold the assets in name only and must follow the beneficiary’s instructions; once the beneficiary is legally able (typically age 18 in England & Wales), they can demand the trust assets/property outright. For tax, HMRC treats the assets as belonging to the beneficiary, so income and gains are taxed on them.

A discretionary trust is more flexible. Beneficiaries are usually a class (e.g., “my children and remoter descendants”), but no one has an automatic right to income or capital. Trustees decide if, when, and how much to distribute, taking account of guidance in a letter of wishes. This can protect assets from beneficiaries’ creditors or divorce, but it is more complex and faces its own trust-level tax regime and possible periodic inheritance tax charges. Hence, the discretion, as the trustees can choose – settlors, the people setting up the trust, can be trustees as well.

In UK trust law, a settlor can be a trustee of the trust they create. There’s no general legal bar on wearing both hats.

But there are important limits and consequences:

Fiduciary duties still apply. Even if they set the trust up, as trustee they must act in the beneficiaries’ best interests and avoid conflicts. If conflicts arise, decisions can be challengeable.

Tax “settlor-interested” issues. If the settlor (or spouse/civil partner) can benefit, income may be taxed on the settlor and some CGT/IHT reliefs can be restricted.

Gift with reservation risk. If the settlor remains a potential beneficiary of a discretionary trust, or keeps enjoying the asset (e.g., lives rent-free in a house put in trust), the asset can still be treated as in their estate for IHT.

Practical tip: it’s common to have the settlor as one trustee, but add an independent co-trustee for balance and cleaner decision-making.

Here’s the UK tax position for a discretionary trust (as at the 2025/26 regime):

Income tax

Trustees pay tax on most trust income at the trust rates: 45% on non-dividend income (interest, rent, trading) and 39.35% on dividend income.

Since 6 April 2024, the old £1,000 “standard rate band” for discretionary trusts has effectively been removed for most cases, so income is generally taxed at trust rates from the first pound (subject to limited exceptions/management expenses).

When trustees distribute income, it carries a 45% tax credit. Beneficiaries then report it and may reclaim some tax if they’re below additional rate.

Knights leaving for Crusades, circa 1170. We hope they had all set up their trusts beforehand.

Capital gains tax (CGT)

Trustees pay CGT on disposals at 24% for residential property gains and 20% for other gains (2024/25 onward).

Trusts get an annual CGT exemption of about half the individual allowance.

Hold-over relief can often defer gains when assets are gifted into or out of a discretionary trust.

Inheritance tax (IHT) – “relevant property” regime

Entry charge: lifetime transfers into a discretionary trust are chargeable lifetime transfers; IHT at 20% may apply on value above the nil-rate band.

Ten-year (periodic) charge: up to 6% of the value above the available nil-rate band at each 10-year anniversary.

Exit charges: when capital leaves the trust, a proportionate IHT charge (also capped at an effective 6%) can apply, based on time since the last anniversary.

Admin / reporting

Trustees must file an annual SA900 trust tax return if there’s tax to pay or HMRC requires it and keep a tax pool / R185s for distributions.

Hopefully, the overview is sufficient for you to consider if a trust might be suitable for you, as opposed to an outright gift to your kids and waiting the seven years; if so, you’ll probably need professional advice.

/3. Have we reached Peak 65? Not old, ‘older’?

My 4-year-old granddaughter is not old, but she is older than her 2-year-old brother; so the adjective changes through time, and we may be older now and that does not mean you and I are old. We’re not. It’s always relative.

The New York Times writer Jason Zeig thinks that perhaps “We have reached Peak 65”.

About 750,000 UK citizens turn 65 each year, compared to around 4 million Americans. Baby boomers will have all sorts of ways to mark the occasion, but underneath the Saga subscription and the usual State Pension jokes lies a niggling unease: the birthday boys and girls will now be officially “old.”

But if there’s still a broadly accepted age at which you become “old” in the UK, it’s 65. For years it was the State Pension age for men and, in practice, the cultural cue for retirement for the past half-century.

It’s odd that we cling to the calendar so deterministically when we age so differently. If you’ve met one 70-year-old, you’ve met one 70-year-old. I’m 66, active, healthy and still working. Yet I’ve recently been outrun at Parkrun and out-lifted at the gym by people in their seventies. As life expectancy stretches on, chronological age says less and less about our physical or cognitive powers.

Sixty-five has served as the default dividing line for old age for so long that it has stopped making sense — and now works against us. It was a label stamped on us by the pension system, and it needs updating.

Think about work and retirement. We’ve been trained to see retirement as something that “should” happen around 65, and that assumption quietly shapes behaviour, expectations and the economy. Mandatory retirement is largely unlawful here, yet we still treat 65 as if it marks a biological cliff edge. It’s a historical hangover.

It started with Otto.

In the 1880s, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck introduced the world’s first state pension. He set retirement at 70 — later lowered to 65 — when average life expectancy was about 40. A minority made it to that age; most did not, which was partly the point. Nearly 150 years on, that benchmark still frames how we think about ageing, even though people in their sixties and seventies are typically far fitter than their predecessors.

You’ve heard the line that 70 is the new 60. Easy to scoff at — except the data suggests even that understates the shift. The clearest long-run evidence comes from Japan, where researchers have tracked older people’s walking speed and grip strength for decades, two standard measures of physical capacity. Over twenty years, both improved sharply. Today’s 75- to 79-year-olds walk faster than people five years younger did a generation ago. Japan is an outlier, but the same pattern shows up across wealthy countries, Britain included.

Calling people “old” too early has real costs. Employers’ instinct to sideline older workers cuts millions off from professional and social networks, increasing the risk of loneliness and isolation. And plenty of older Britons absorb the message that decline is inevitable, simply because that’s the story we’ve repeated for decades.

The Yale psychologist Becca Levy has found that older adults who internalise negative stereotypes about ageing are less mobile, have poorer memory, recover more slowly from illness and injury, are more prone to cognitive decline, and die on average 7.5 years earlier than peers with more positive views of ageing.

All of which leaves awkward questions. If 65 no longer means “old”, does 70? 75? Do I need to hand back my Freedom Pass if I’m still working and feeling good? Can I keep claiming my state pension? I’ll keep the Railcard, thanks — but I’m done with the idea that there’s a single, universal line between middle age and old age. There needs to be a sliding age / scale for retirement for the following reasons:

It’ll encourage and support people to work longer, as they may wish, rather than have the ‘at 65/66/67’ age indelibly etched.

It’ll delay some people from claiming state pension, saving the Chancellor money.

It’ll keep some of the country’s most experienced people in the workforce.

For childcare, social care and geriatric care, these are the hands-on experienced experts.

This solves the cliff edge impact on wellbeing for retirees who struggle with the lack of structure and routine after employment.

If we have 750,000 turning 65 every year, if we can find a route to bringing, say 20%, back into the work force for, say, two further years, then over the first five years we’ll have ‘found’ an extra work force equal to 1.35 million worked years, 310 million man days. That’s a lot of money earned, and a lot of state pension saved.

/4. Look at a trust: why we love Law Debenture

It’s unique.

Here’s what’s genuinely distinctive — and attractive — about Law Debenture (LWDB).

What’s great / interesting facts

A rare “two-engine” model. LWDB is both a UK equity income investment trust and owner of a profitable Independent Professional Services (IPS) business (pensions trusteeship, corporate trust, governance, etc.). That IPS arm is about c.19% of NAV and throws off recurring, relatively non-market-linked profit.

Long history + low costs. Listed since 1889 (135+ years) with ongoing charges around 0.48–0.51%, well below sector averages.

Contrarian, quality-value style. Managers aim to buy good UK companies when they’re out of favour, rather than hugging the index.

How resilient are the dividends?

Exceptionally. LWDB has 46 years of maintaining or increasing its dividend, and the board has signalled intent to extend this (to 47) for 2025.

Why that resilience?

IPS smooths the cycle. IPS has funded roughly a third of dividends over the last decade, giving a buffer when portfolio income is under pressure.

Revenue reserves + flexibility. The trust can hold lower-yield / growth names and avoid “yield traps” because IPS contributes to income.

Capital growth / total return

Share price total return (incl. dividends reinvested):

10 years: +158.7%

NAV total return (debt & IPS at fair value):

10 years: +137.1%

The 25 year total return for Law Debenture is 9.25% per annum, 10 year is 8.21%. That’s strong real-world capital growth for a UK income trust. If you bought the shares 25 years ago, your yield to cost is now 14.34%, and by 2018, you had all your original purchase cost repaid by dividends.

The 2000 dividend was 6.8p, the 2024 was 33.5p – it has been growing the income paid to shareholders at almost 7% per year.

CAGR = (33.5/6.8) 1/24 − 1 ≈ 6.9% per year

For 2024 year-end, it had £47.5m in revenue reserves, plus £43.8m in revenue, totalling £91.3m in firepower to support a total dividend of £43.6m.

We love the team, we love the trust.

/5. Fancy some crypto? How to lose your shirt, or, what they don’t tell you.

It’s all about timing, investment usually is. The trouble is that you’ll rarely see adverts telling you to sell an investment, only to buy. (See last week’s blog – newspapers only exist to service advertising).

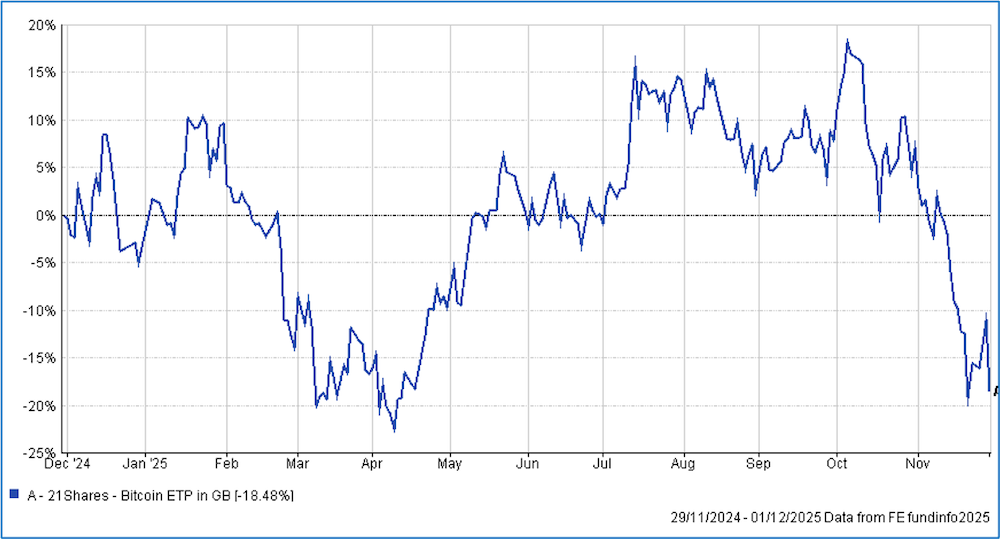

This is what the positive commentary will show you about Bitcoin:

This is what the investor got this year:

Same investment, same story, same theories, yet the two charts are very different. For one, in the top I ran the data on quarterly changes and on the bottom on daily, hence the extreme jaggedy-ness. But then, how often do you think Bitcoin traders look at their Bitcoin? Daily? Yes, most probably. What do you think the spiky chart does to the emotions? What is the difference between how an investor would view these charts and how a trader would?

As I said above, anything we don’t understand, we put out or leave to third parties, and we really don’t understand bitcoin. Stablecoins perhaps, and there is a real need that most can see for a digital form of currency so banks don’t need to pass wadges of the folding stuff between each other. It used to be said that crypto was secure because of the visibility, hence the need for it to exist, but that has been proven to be quite wrong.

Call us old-fashioned, but we like to stick to our knitting.